Increasing Security Using Women’s Police Stations: Argentine and Brazilian Case Studies

August 21, 2023

As an advocacy organisation, SecurityWomen promotes the increased representation of women in police, military, and peacekeeping forces – with the goal of changing the culture of these institutions and structures to improve overall security. Both Argentina and Brazil’s implementation of women’s police stations, where policing is only by women and where only victims of male violence are received, provide interesting case studies to show exactly how society can benefit from a new policing culture...one that is not hyper-masculinised.

Notably, according to the United Nations, Argentina had the highest ratio of police officers to citizens in the Latin American region in 2018, at nearly 795 officers for every 100,000 citizens. Impressively, while the global average for the number of women police officers sits at 15.4 percent, Argentina boasted just over 40 percent that same year. It is important, however, to qualify this statistic, noting that advancement for women officers is comparatively lower than that of their male counterparts. And so, police leadership remains predominantly male.

That being said, Argentina was home to its first all-women police brigade in 1947 and the Buenos Aires Province implemented the country’s first women’s police station in 1988. This came just five years after the country’s official return to democracy post-military dictatorship – which was characterised by a brutal and violent campaign of repression in which many civilians disappeared. Women were particular targets during this campaign, with military enforcers adopting SGBV as a tool against dissidents to maintain and stabilise the regime. Many young women in detention fell pregnant as a result of this torture, that used rape as a tool, and were ultimately executed after giving birth, forced to give up their babies to families of the political elite – grassroots organisations led by the grandmothers of these babies continue to investigate these cases to reunite the separated children with their surviving families. This period of government-sanctioned SGBV was also characterised by a culture of masculine militarism. And so, in the late 1980s, the government turned to the Brazilian concept of women’s police stations – first used in the neighbouring country in 1985 – to reduce SGBV in the country by introducing a parallel police force with an entirely new and different structural culture.

Currently, there are 128 women’s police stations, or Comisaría de la Mujer, in the Argentine capital of Buenos Aires alone, staffed by approximately 2,000 women officers. While they collaborate with and do much of the same work as the ordinary Argentine Federal Police (PFA), these women approach their work very differently and have a much broader mandate.

The first give-away is the police buildings themselves. Rather than the stoic and intimidating buildings of the PFA, the women’s police stations are colourful and inviting, home to interdisciplinary teams. Rather than being structured to deal with criminal offenders, the buildings themselves are designed to accommodate victims – particularly victims of SGBV. Instead of custodial cells, women’s police stations offer psycho-social support – both onsite and online –, childcare facilities, as well as programmes to rehouse and offer alternative financial support for women looking to leave abusive partners. And so, not only are these officers the first responders to and the investigative partners of the prosecuting authority when it comes to SGBV cases, but they also have a strong preventative mandate.

To fulfil this preventative mandate and to help end the cycle of SGBV, officers remain very active and visible in the community – patrolling all over the capital city. Around every block or so in the downtown area, you can find these women in their signature blue and black uniforms, either handing out SGBV information flyers, or checking on any unaccompanied children and any women that appear to be in distress. They are also involved in public education projectsaimed at improving awareness of what SGBV looks like and how to seek help. As a result, the women of the Comisaría de la Mujer are trusted members of the community.

This stands in stark contrast to how the community perceives the PFA. For instance, as recently as June 2023, there were violent clashes between the PFA and protestors in the Jujuy province over constitutional reforms that critics argue restrict the right to social protest. Many officers have also been implicated in corruption, abuses of authority, and collusion with organised crime and trafficking, contributing to a negative community perception of PFA officers.

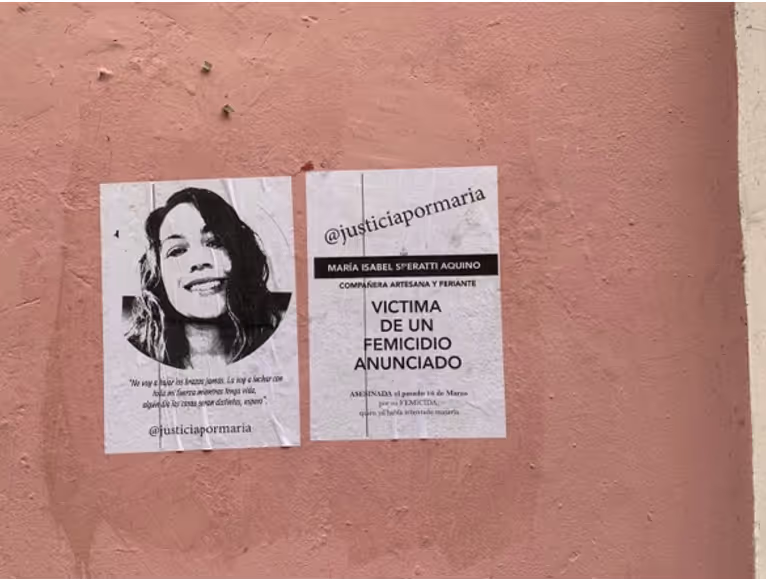

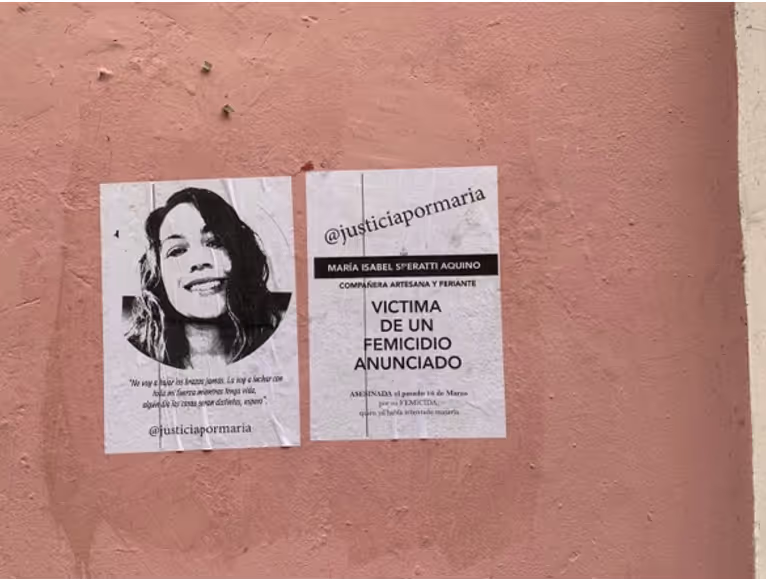

That being said, there is no data to support that women’s police stations in Buenos Aires have led to lower SGBV or femicide levels – and therefore increased overall security. Sadly, Argentina continues to report high femicide rates, recording more than 250 in 2020, 2021 and 2022 – an average of one femicide every 35 hours. In the province of Buenos Aires alone, authorities recorded one femicide every 96 hours in 2022. In March 2023, public outcry on the topic of femicide and SGBV in Buenos Aires peaked after María Isabel Speratti Aquino was shot and killed by her ex-partner while taking her children to school – after she survived his first murder attempt in 2021 and after two years of asking the authorities for protection.

There is, however, evidence of the positive influence of women’s police stations in Brazil. While 699 femicides were recorded in 2022, researchers in Brazil found that in the areas with women’s police stations, the female homicide rate for women aged between 15 and 24 dropped by 50 percent, and for all women by 17 percent.

This is particularly interesting given Brazil has a much lower ratio of police officers to citizens than Argentina. As of 2020, Brazil had 480,000 civil and military police officers on active duty – working out to 225 police officers per 100,000 inhabitants, 14% of which were women. Moreover, there are increasing concerns regarding the violent culture of Brazilian police, particularly regarding the number of deaths during police operations in the country. For instance, in 2022, 17 people died per day in police operations in the country – totalling 6,429 deaths. Forty-five people were killed in the first week of August 2023 in the Bahia and Sao Paulo states alone.

This culture of violence is unsurprising when observing how well-armed police officers are when patrolling the streets in Brazil. In fact, it is commonplace to see police officers carrying two pistols each when patrolling even the wealthiest of areas in the touristic Rio de Janeiro. To better understand this culture, most attribute the lethal nature of police operations to the Brazilian state’s aggressive war on drugs. While the vast majority of police killing victims are young men of colour, cis and transgender women are also particular targets of other various forms of violence.

And so, while Argentina and Brazil provide two very different contexts – with the former boasting a much higher ratio of police to civilians, as well as of women to men in policing, and with the latter boasting higher femicide and police killing rates – both states have implemented women’s police stations to curb SGBV rates. Ultimately, Brazil having far fewer police per inhabitants than Argentina, and having a particularly violent police culture, regions with women police stations still saw a significant decrease in femicides in the country – particularly amongst young women.

Many other countries have since found the value in women’s police stations when trying to curb SGBV and femicide rates. Specific examples of countries that have implemented similar police stations include – to varying degrees – Bolivia, Nicaragua, Peru, Uruguay, Sierra Leone, India, Ghana, Kosovo, Liberia, the Philippines, South Africa and Uganda.

August 21, 2023

Increasing Security Using Women’s Police Stations: Argentine and Brazilian Case Studies

August 21, 2023

As an advocacy organisation, SecurityWomen promotes the increased representation of women in police, military, and peacekeeping forces – with the goal of changing the culture of these institutions and structures to improve overall security. Both Argentina and Brazil’s implementation of women’s police stations, where policing is only by women and where only victims of male violence are received, provide interesting case studies to show exactly how society can benefit from a new policing culture...one that is not hyper-masculinised.

Notably, according to the United Nations, Argentina had the highest ratio of police officers to citizens in the Latin American region in 2018, at nearly 795 officers for every 100,000 citizens. Impressively, while the global average for the number of women police officers sits at 15.4 percent, Argentina boasted just over 40 percent that same year. It is important, however, to qualify this statistic, noting that advancement for women officers is comparatively lower than that of their male counterparts. And so, police leadership remains predominantly male.

That being said, Argentina was home to its first all-women police brigade in 1947 and the Buenos Aires Province implemented the country’s first women’s police station in 1988. This came just five years after the country’s official return to democracy post-military dictatorship – which was characterised by a brutal and violent campaign of repression in which many civilians disappeared. Women were particular targets during this campaign, with military enforcers adopting SGBV as a tool against dissidents to maintain and stabilise the regime. Many young women in detention fell pregnant as a result of this torture, that used rape as a tool, and were ultimately executed after giving birth, forced to give up their babies to families of the political elite – grassroots organisations led by the grandmothers of these babies continue to investigate these cases to reunite the separated children with their surviving families. This period of government-sanctioned SGBV was also characterised by a culture of masculine militarism. And so, in the late 1980s, the government turned to the Brazilian concept of women’s police stations – first used in the neighbouring country in 1985 – to reduce SGBV in the country by introducing a parallel police force with an entirely new and different structural culture.

Currently, there are 128 women’s police stations, or Comisaría de la Mujer, in the Argentine capital of Buenos Aires alone, staffed by approximately 2,000 women officers. While they collaborate with and do much of the same work as the ordinary Argentine Federal Police (PFA), these women approach their work very differently and have a much broader mandate.

The first give-away is the police buildings themselves. Rather than the stoic and intimidating buildings of the PFA, the women’s police stations are colourful and inviting, home to interdisciplinary teams. Rather than being structured to deal with criminal offenders, the buildings themselves are designed to accommodate victims – particularly victims of SGBV. Instead of custodial cells, women’s police stations offer psycho-social support – both onsite and online –, childcare facilities, as well as programmes to rehouse and offer alternative financial support for women looking to leave abusive partners. And so, not only are these officers the first responders to and the investigative partners of the prosecuting authority when it comes to SGBV cases, but they also have a strong preventative mandate.

To fulfil this preventative mandate and to help end the cycle of SGBV, officers remain very active and visible in the community – patrolling all over the capital city. Around every block or so in the downtown area, you can find these women in their signature blue and black uniforms, either handing out SGBV information flyers, or checking on any unaccompanied children and any women that appear to be in distress. They are also involved in public education projectsaimed at improving awareness of what SGBV looks like and how to seek help. As a result, the women of the Comisaría de la Mujer are trusted members of the community.

This stands in stark contrast to how the community perceives the PFA. For instance, as recently as June 2023, there were violent clashes between the PFA and protestors in the Jujuy province over constitutional reforms that critics argue restrict the right to social protest. Many officers have also been implicated in corruption, abuses of authority, and collusion with organised crime and trafficking, contributing to a negative community perception of PFA officers.

That being said, there is no data to support that women’s police stations in Buenos Aires have led to lower SGBV or femicide levels – and therefore increased overall security. Sadly, Argentina continues to report high femicide rates, recording more than 250 in 2020, 2021 and 2022 – an average of one femicide every 35 hours. In the province of Buenos Aires alone, authorities recorded one femicide every 96 hours in 2022. In March 2023, public outcry on the topic of femicide and SGBV in Buenos Aires peaked after María Isabel Speratti Aquino was shot and killed by her ex-partner while taking her children to school – after she survived his first murder attempt in 2021 and after two years of asking the authorities for protection.

There is, however, evidence of the positive influence of women’s police stations in Brazil. While 699 femicides were recorded in 2022, researchers in Brazil found that in the areas with women’s police stations, the female homicide rate for women aged between 15 and 24 dropped by 50 percent, and for all women by 17 percent.

This is particularly interesting given Brazil has a much lower ratio of police officers to citizens than Argentina. As of 2020, Brazil had 480,000 civil and military police officers on active duty – working out to 225 police officers per 100,000 inhabitants, 14% of which were women. Moreover, there are increasing concerns regarding the violent culture of Brazilian police, particularly regarding the number of deaths during police operations in the country. For instance, in 2022, 17 people died per day in police operations in the country – totalling 6,429 deaths. Forty-five people were killed in the first week of August 2023 in the Bahia and Sao Paulo states alone.

This culture of violence is unsurprising when observing how well-armed police officers are when patrolling the streets in Brazil. In fact, it is commonplace to see police officers carrying two pistols each when patrolling even the wealthiest of areas in the touristic Rio de Janeiro. To better understand this culture, most attribute the lethal nature of police operations to the Brazilian state’s aggressive war on drugs. While the vast majority of police killing victims are young men of colour, cis and transgender women are also particular targets of other various forms of violence.

And so, while Argentina and Brazil provide two very different contexts – with the former boasting a much higher ratio of police to civilians, as well as of women to men in policing, and with the latter boasting higher femicide and police killing rates – both states have implemented women’s police stations to curb SGBV rates. Ultimately, Brazil having far fewer police per inhabitants than Argentina, and having a particularly violent police culture, regions with women police stations still saw a significant decrease in femicides in the country – particularly amongst young women.

Many other countries have since found the value in women’s police stations when trying to curb SGBV and femicide rates. Specific examples of countries that have implemented similar police stations include – to varying degrees – Bolivia, Nicaragua, Peru, Uruguay, Sierra Leone, India, Ghana, Kosovo, Liberia, the Philippines, South Africa and Uganda.